- Home

- Rae Richen

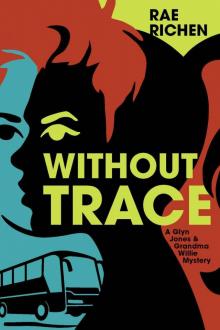

Without Trace

Without Trace Read online

Without Trace

A Glyn Jones and Grandma Willie Mystery

by

Rae Richen

Without Trace

A Glyn Jones and Grandma Willie Mystery

Copyright@ 2021, by Rae Richen All rights reserved.

Published in the United States of America by

Back Beat Publications

an imprint of Lloyd Court Press

3034 N.E. 32nd Avenue

Portland, Oregon, 97212

www.lloydcourtpress.org

Cover design by Diana Kolsky

Book Design by S.R. Williams

Paper ISBN: 978-1-943640-13-3

E-book ISBN: 978-1-943640-14-0

While inspired by actual societal situations, this is a work of fiction. All characters and incidents in this book are fictionalized by the author. Other than Willie, perceived resemblance to people, living or dead, business establishments, events or locales is purely coincidental.

Publisher’s Cataloging-In-Publication Data

(Prepared by The Donohue Group, Inc.)

Names: Richen, Rae, author.

Title: Without Trace / Rae Richen.

Description: Portland, Oregon : Back Beat Publications, an imprint of Lloyd Court Press, [2021] | Series: A Glyn Jones and Grandma Willie mystery ; [1]

Identifiers: ISBN 9781943640133 (paperback) | ISBN 9781943640140 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Young Adults, Drummers (Musicians)—Crimes against—Pacific States—Fiction. | Kidnapping—Pacific States—Fiction. | Rescues—Pacific States—Fiction. | Organized crime—Pacific States—Fiction. | Grandmothers and Grandsons—Pacific States—Fiction. | LCGFT: Detective and mystery fiction.

Classification: LCC PS3618.I3455 W58 2021 (print) | LCC PS3618.I3455 (ebook) | DDC 813/.6—dc23

Dedication

To Clifford and Wilhalmena Williams for showing us how to create a life of infinite interests and of care for all who surround us. Thank you for leading the way.

Table of Contents

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

ChapterTwenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Chapter Twenty-five

Chapter Twenty-six

Chapter Twenty-seven

Chapter Twenty-eight

Chapter Twenty-nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-one

Chapter Thirty-two

Chapter Thirty-three

Chapter Thirty-four

Chapter Thirty-five

Chapter Thirty-six

Chapter Thirty-seven

Chapter Thirty-eight

Chapter Thirty-nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Epilogue

Chapter About the Author

Chapter Truckers Against Trafficking

Chapter Help to Stop Human Trafficking

Chapter Other Novels by Rae Richen

Chapter One

Trace and Taco Bell

Sixteen-year-old Glyn Jones swerved the Camry over to the curb at the corner of Interstate Avenue and Killingsworth Street, Portland, Oregon. His passenger, Trace Gowen yanked open the door.

“Thanks, Man,” Trace mumbled.

“You on something again?” Glyn asked.

Trace laughed the high laugh that Glyn knew too well. The laugh alone made a lie of anything Trace said.

“Go home and clean up.” Glyn put the Camry back in drive.

Trace took the hint and climbed out, not too smoothly. He caught one long dred lock on the window handle, yanked it out, and missed the door handle twice before he got the car door closed.

Glyn glanced at the trash Trace had left on the floor of the car, a sack of Taco Bell wadded and crushed, an empty paper cup, rolling around on the floor mat. He decided not to get Trace to clean it up. Getting him out of the car became more important. Lately, Trace seemed to be on one drug or another and Glyn wanted the smell of it out.

Glyn hoped the pop container was empty. This was Mom’s car.

He signaled a turn, pulled into the lane, and headed toward home. He passed the corner on Fremont and Fifteenth where he’d picked Trace up and wondered why Trace had been wound up tight. Five miles up Fremont Street, he heard his cell. He pulled it out of his pocket, swiped the face and answered, “Lo?”

He punched the speaker phone button and dropped it on the seat, wishing he’d hooked it up to the Bluetooth in this car. “What up?”

“Bring me my stuff.” Trace shouted.

“What stuff?”

“They’ll kill me, Man.”

“What stuff? Where?”

“In the Taco Bell. Hurry.” Trace’s voice cut off.

Trace’s fear invaded Glyn’s cocoon. He flipped around the next corner to the right, roared around the block and came out at a traffic light on Twenty-Fourth Avenue. At this hour, no one drove on Fremont, and he sat first in line, so he ignored the red, and angled into Fremont going back toward Trace. He felt the sweat on his hands as he smacked on his horn, urging the slow Volvo in front of him to regulation speed. Finally, he passed the old geezer and roared down the street hoping to make the green at Fifteenth.

He glanced down at the crushed bag. He didn’t even want to know what was in it. Clearly, Trace had been sampling. Another problem the guy would face.

Last week’s effort by the guys in the rap group had failed to get Trace to leave the drugs alone. Trace had heard nothing, cared less, and now he’d pay for it, big time.

Glyn and the Camry flew through the yellow at Fifteenth Avenue. At Eighth, he heard the siren.

“Hot damn.” Glyn pulled to the right and parked. His mother’s voice whispered in his head.

“Be polite, but don’t over-do it. People suspect too polite.”

How did Mom know that? He’d never asked, too embarrassed that she guessed he needed the advice.

He rolled down his window and waited. The policeman opened his car door and approached the Camry.

“May I see your license?”

“Sure. It’s in my back pocket.” Glyn knew the police were always looking for kids to reach for guns. He heard enough stories from the rap group. That was how Markus’s cousin ended up on a respirator. Glyn had the advantage of being white, but he also was under twenty, so who knew what ideas ran in this cop’s head.

“Well, get it out,” the officer said.

Glyn left his right hand on the steering wheel, rolled his butt up and reached into his left back pocket for his wallet. He handed it to the officer and tried hard not to glance at the Taco Bell. The officer flipped open the wallet and examined the photo ID.

“Cut your hair?”

“Yeah. Shaggy.”

“A little early in the day for fast food, don’t you think?”

Glyn finally took a moment to survey the sack on the floor. “I love grease,” he said. “No grease in Mom’s oatmeal.”

“Don’t I know. You ran a red and then a yellow and I clocked you at fifty-five in this thirty zone.”

“Yeah, suppose I did all that.”

“Ticket for that is expensive, my friend.” And the patrolman ripped an already written t

icket off his pad.”

“Jones, eh?” the officer said, staring once more at the ID. “Why the funny spelling for Glyn?”

“Those Welsh. They love the letter Y.”

“Yeah, well drive the speed limit. You’re pushing this old Camry beyond its capacity.”

“Yes, sir.”

The officer returned to his car, plopped inside, slammed his door and appeared to be making notes. Glyn waited a couple of seconds, to make sure he was dismissed. He imagined Trace standing on the corner of Interstate and Killingsworth, imagined all the cars in and out of the local Chevron, where they often met to use the back room for recording their rap beats.

He imagined Trace waiting while the MAX, Portland’s light-rail trains, hunkered north and south, stopping, rolling, stopping, rolling. He imagined the thugs Trace feared. In his mind, they pulled to the curb and Trace stood alone, without product.

He held the Camry to thirty until out of police sight, and then gunned it.

At Interstate and Killingsworth, Trace was not standing on the corner, none of the corners, nor the MAX platform, nor in the filling station.

Felipe, manager of the filling station, said, “I ain’t seen him. Nothing.”

But Felipe surveyed the other attendants as he said this, and never looked at Glyn. The other guys and the one gal glanced away and wouldn’t make eye contact either. They all knew Trace, drummer of the Ancient Nation rappers. And they knew Glyn and his computer-generated beats for the group. The guys and Anita looked tense, scared.

Glyn decided to let Felipe off the hook, and said, “Must have gone home. Can you give me a ten’s worth of regular?” He handed Felipe a five, and five ones.

Felipe nodded and let air out of his tight body. As Felipe stuffed the hose into the Camry, Glyn called Trace’s phone and got the forwarding message. Not even on. Then he checked his own phone. Trace had left a text.

“There commin.”

He knew it was Trace. The guy never bothered with spelling distinctions. Glyn grabbed the trash from the floor and climbed out of the car. He started to toss the sack into the garbage can, but Felipe reached out.

“We recycle paper here,” he said.

“Okay,” Glyn handed him the bag, well-aware that old food bags were not recycled in Portland. He said, “Trace needs your help, Felipe.”

“Not seen Trace, I tell you.”

“All right. Whatever.”

Felipe clicked off the gas nozzle. “That’s a ten’s worth of Gas.”

“See you at rehearsal time. Maybe Trace’ll show.”

“Can’t have you rehearsing here this afternoon.”

Glyn studied Felipe and the others. “I’m outta here then.”

Chapter Two

None of the guys had seen Trace since the Taco Bell situation the day before. Twenty-four hours and the Ancient Nation members had pressed all their connections. They’d come up blank. The guy was gone. They feared gone, as floating in the river, but none of them said it.

Leneld came closest to it. “Wish he’d just stepped into Darrell’s Bar on the corner.”

“Darrell wouldn’t stand up to guys like that,” Glyn said.

“Yeah. Not for some strung-out black kid who was scared,” Leneld added.

The guys were all afraid. Afraid for Trace and afraid to push the wrong buttons on the wrong people who might explode on them and on the people they loved.

The other consequence of Trace’s disappearance was the loss of practice space, so the guys met now in Glyn’s basement.

Which was good because that’s where Glyn’s computer sat, and if they were practicing, he could be writing beats for them at the same time. Easier to do on this computer than the laptop he took to the filling station garage.

Of course, today, there was no music happening. They were trying to figure out how to get Trace back safely.

With Dad off being a mathematician for an insurance company, and Mom designing gardens from her office on the second floor, they could talk pretty freely, as long as they stuffed the laundry chute with old sheets and fabric from Mom’s quilting stash. Glyn knew she never used the grayed-down fabric other quilters gave her, so they stuffed in those dull fabrics. They’d decided they would un-stuff the chute at the end of this meeting and hide the material in a bag in the furnace room for future meetings.

Mom’s office was in the room at the top of the chute, and she had good ears. Susan Stamps Jones was that rare designer who never listened to music while drawing gardens and deck-building details. So, her office had all the acoustic possibilities the band didn’t need during serious talks.

Glyn studied the guys. Leneld, who always called it like it was. Danny, always eager to please, because Dan was a white wanna-be. Markus, tall, flamboyant, sure, great with the artwork for posters and album covers.

Missing was DeAndre who hadn’t shown up since the Taco Bell incident and was probably lying low for reasons only others could guess.

“Danny,” Glyn said, “From now on, can you help me un-stuff the chute when we adjourn? Easier for two.”

“Adjourn? Where do you get these words? You’re a twit, Glyn.”

“Twit or not, you got a job.”

“Maybe,” Danny said.

Leneld said, “You got a job, Dan.”

Dan slumped. “ ‘kay.”

“We gotta figure Trace’s last movements again,” Markus said.

Leneld went over it. “His mom says you picked him up at their house, Glyn. You say he came out with the Taco Bell and actually ate the burritos in your car, so why do you think he had product in there?”

“It weighed.”

“What? A kilo?” Markus asked, twiddling his drawing pen.

“I got no idea what a kilo weighs,” Glyn said. “You see a druggie scale down here?” .

“Okay, weighed something,” Leneld went on. “And you dropped him at the corner because . . .?”

“He asked. Assumed he was fiddling with his drum set before rehearsal.”

“But, later, when you tried to toss the Taco Bell, Felipe wanted it,” Markus said. “Why’d you hand it over?”

“Yeah, so I figured he knew, and had a way of getting it to Trace.”

“Maybe he just wanted it for himself,” Danny said.

“Felipe’s not the druggie type,” Glyn said. The others nodded.

“He’s afraid of the stuff,” said Leneld, “and for good reason.”

“Did you ask about the drum set?” Markus asked.

Tall, gangly Leneld said, “Felipe unloaded those into my car this morning. Couldn’t get rid of them fast enough.”

“We can help unload later,” Markus said.

Glyn said, “I got the speakers and the other crud yesterday afternoon. But the weirdest thing . . . Felipe, Anita and the guys had them all packaged up and hidden behind the tire sales area. It was like they were hiding them for us.”

Leneld said, “Whoever got Trace woulda sold that stuff if they knew. Felipe saved our butts.”

“How’s your Mom gonna be about all this noise?”

“She’s down with it,” Glyn said.

“Yeah,” said Danny. “She’s off digging in people’s gardens half the day, anyway. No skin off her teeth.”

Glyn stared at Danny and said, “She did say there were rules.”

“Rules? Shit, Man!”

“Rule one: Don’t use words your grandmother wouldn’t approve of, and she knows your grandmothers.”

“Not mine,” Danny said, “She’s in the House.”

“Actually,” Glyn said, “my grandmother knows your grandmother. Grandma Willie teaches writing for Corrections.”

“My grandma don’t write.”

Glyn raised his eyebrows at Danny.

Danny said, “No way. She’s writing about me?”

“Remains to be seen. Anthology coming out next spring.”

“Jeeezus.”

Markus asked, “What’s the second rule?”

&

nbsp; Glyn nodded. “Rule two: Don’t eat anything that has a ‘don’t eat me’ sign on it.”

“That’s sort of weird.” Leneld said. “You’d think it’d be easier to mark the ‘do eat me’ stuff.”

“Way my mom thinks,” Glyn said. “She figures we’ll eat anything, so just labels the really don’t- eat-me stuff. She stores seeds in the fridge, you know.”

“Why?”

“No clue. Calls it scarifying them.”

Leneld laughed. “Scarifying us, for starters.”

**

Over the next hour, the guys tried to come up with sources of possible information about Trace: where he might have been before he stuffed product in the Taco Bell bag; who he might have gotten it from – a list that Danny was able to provide, a very iffy list, but Leneld and Markus were willing to look into his supposed street connections. They thought maybe some of those sources could tip them off to Trace’s supply guy.

“Supply guy or gal,” Glyn said.

“Yeah, yeah,” Markus said.

But Leneld emphasized the idea. “Or gal. Watch your prejudices, Markus.”

Markus snorted, and held up a drawing of Trace. It was perfect, right down to the long and short dred locks. “Let’s find him.”

They duplicated the drawing, and each took some copies.

**

The more iffy meeting for Glyn, was that afternoon. He signed into the visitors’ desk at Holly Hills Retirement Center and took the elevator to the eighth floor. He stood a moment outside the door of eight-twelve, the door with the aromatic wreathe of dried eucalyptus leaves and the name, ‘Wilhalmena Stamps’ on the door. He straightened his shirt, hitched up the draggy pants and knocked.

Inside the door, he heard his grandmother shuffling, imagined her laying down whatever book she read, and pushing her walker around the coffee table filled with magazines and Readers’ Digest contest entries. Moments later, her door opened.

“Ah. My favorite recalcitrant,” she said. “Explain to me about this three-hundred-dollar speeding ticket.” She stepped back to let him in.

Glyn knew not to say anything about Trace, the Taco Bell or the extra stuffing in the burrito bag. Grandma talked to police. She taught writing at the main community college where policemen got their training. She taught at the corrections facilities. She recognized bullshit at five miles. At five-foot-two leaning on a walker, Grandma Willie was not to be messed with.

Without Trace

Without Trace